How Poppy Fields Turned Tea Gardens

The Royal Development Projects

“Great things come from small beginnings.

A gentle ripple starts from just a single drop.

That wave ever expanding, with no end in sight,

Begins from one very small point, our own self.”

To understand how poppy fields turned tea gardens in North Thailand in relatively little time, and how the targeted cultivation, processing and marketing of tea (Camellia Sinensis) started at all, we will first have to gain some insight to the situation in North Thailand at the beginning of the 1950ss as well as to the origins and the character the Royal Thai Development Projects.

Situation in North Thailand during the 1950s and 1960s

Hall of Inspiration exhibits, Royal Development Project, Doi Tung

Hall of Inspiration exhibits, Royal Development Project, Doi Tung

At time of King Bhumbol Adulyadej’s (also Rama IX.) accession to the throne on June 9, 1946, a reign that should last for more than 6 decades and still ongoing, large parts of North Thailand and North East Thailand were widely isolated from Bangkok at the surrounding Central Thailand through geographic, infrastructural and cultural barriers. The inhabitants of north Thailand, the bordering region to Burma, consist of an ethnic variety of North Thais, Shan, Chinese and the members of a number of different mountain tribes that partially maintain their own distinct cultures and languages until today.

One of the consequences of the infrastructural isolation was a blatant “wealth gap” between Bangkok and Central Thailand on the one side, and North and East Thailand on the other. From the 1960s on, one way out of poverty was offered by the cultivation of the opium poppy and its processing to heroin, which then was brought via Bangkok to the Western, especially the US market. A second income alternative opened up for women: the way into prostitution.

In those times, especially the mountain tribes pursued a nomadic lifestyle, accompanied by the slash and burn agricultural style that is typical for this lifestyle. Their bamboo hut villages were quickly reestablished on any new site. What they left behind, were cleared, depleted, burnt landscapes. Where they went, the trees always were the first thing to give way.

The Royal Thai Development Projects

“We will reign with righteousness for

the benefit and happiness of the Siamese poeple.

“King Bhumibol Adulyadej on his development journeys through the country

“King Bhumibol Adulyadej on his development journeys through the country

At the beginning of the 1950’s, king Bhumibol started an intensive program, in whose context he traveled the country tirelessly for decades to its remotest corners to assess the situation and problems of the people on site by himself, consider possible options for remedy and improvement, and then initiate and accompany the identified measures. The comprehensive series of projects resulting hereof are summarized under the umbrella term Royal Development Projects. The projects cover a wide range of economical and social infrastructure areas, namely agriculture, environment, public health, promotion of employment and small enterprise culture, water resources, communication, public welfare, and more.

What makes the Royal Development Projects in Thailand stand out from comparable public projects worldwide in a positive way, are

- the genuine character of the underlying motivation (instead of a mere social and economic policy alibi or development policy reputational function)

- the orientation at actual requirements, conditions and possibilities surveyed by king himself on site, and

- the humanist concept of the human being, seeing people as products, i.e. in the case of deficiency also as a victim of their environment, and not as the cause of the deficiency in terms of being the culprits. Accordingly, the credo of the idea is the positive change of the resources situation with regard to education, skill development, health, traffic and communication infrastructure, environment, ownership of land and production means, and public awareness in order to create the needed basis for a sound society and a flourishing economy.

Besides the projects initiated and accompanied by King Bhumibol himself, amongst these six development study centers distributed all over the country for conducting surveys, research and experiments for the creation of development guidelines and methods in adaption to the respective conditions and initial situation in each part of the country, the Royal Project also supports individual and public efforts deemed as valuable by the king.

Poppy Cultivation and Opium Processing in North Thailand

Doi Tung Royal Development Project: Hall of Inspiration, Opium Exhibit

Doi Tung Royal Development Project: Hall of Inspiration, Opium Exhibit

Until well into the 1960s, the cultivation of the opium poppy the use of the derived opium for medical purposes as well as a everyday means of leisure and recreation, were more or less an integral part of the daily life of many of the Northern Thai mountain people. In a way, one could say that though the cultivation and consumption of opium was an integral part of the culture of a large part of North Thailand’s mountain population in those times, it was also controlled and kept withing socially acceptable limits by exactly that culture. This fundamentally changed from the middle of the 1960’s.

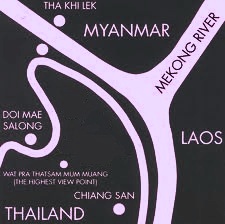

The Golden Triangle, in geographic terms the border triangle of Thailand, Burma and Laos, had begun earning a worldwide reputation as a production center and source for the heroin traded in the west, especially on the North American market. What had long been considered as a conspiracy theory, today is a widely accepted historic fact: against the backdrop of the Vietnam war, the American secret service CIA itself became one of the key players in the international drug trade. The complex and sensitive mesh of mutual and conflicting interests, and the resulting alliances and enemies in South East Asia, had to be maintained (and financed!). If we track the career of the region’s most notorious drug kingpin and warlord, Khun Sa, alias Chang Chi Fu, son of a Chinese father and a Shan mother, from a US ally to America’s Public Enemy Nr. 1, we will hardly miss the parallels to the more recent historical events around the character of Osama bin Laden.

During the 1950s, as a consequence of the victory of Mao Tse Tung’s “cultural revolution” in China, a large group of ethnic Chinese, former military opponents of Mao that had now become persecutees of the new communist regime, had migrated to North Thailand via Burma. These Chinese refugees had established a notable series of settlements in the Northern Thai mountains, the largest and best known of which is is Doi Mae Salong. Thanks to their connections and backgrounds, the Chinese soon seized a proactive role on the new market and became key players in the organization of opium cultivation, processing and trade not only limited to North Thai terrain, but also cross-border. Other mountain tribes of the region, many of them, such as the Hmong, with their origins in China, who had been living as hunters, collectors and farmers so far, were only too eager to jump on the train and secure their own slice of the cake of the new alleged prosperity.

Opium Poppies, Poppy Field, in Noth Thailand, Golden Triangle

Opium Poppies, Poppy Field, in Noth Thailand, Golden Triangle

This situation soon turned into a devastating one for the Northern Thai mountain population: Not only did the drug money ultimately hardly benefit the general population or region at all, but much rather was transfered offshore by the few major profiteers, the resulting mass addiction to opium and heroin in the uneducated and unknowledgeable population also left the picture of misery upon the villages and communities.

It were these conditions situation and this misery that the Thai King found on his journeys to the North, and despite the apparently overwhelming challenge, he was firmly determined to shun no effort to change this picture from the ground up. Now, of course, opium could be declared illegal, and the relevant law enforced by means of police and military forces, and even this was done, but ultimately, how sustainable will blindly and against the people’s will enforced changes be, and what was to fill the economic and social hole that the discontinuation of opium production, trade and consumption would inevitably bring about?

Today, as a consequence of the large scale Royal development projects in terms of economic sustainability, environmental soundness, social and economic balance as well as the establishment of a generally accessible education infrastructure, we see the traces of North Thailands historic role as a part of the infamous Golden Triangle practically only in museums. An example for the targeted, worldwide unprecedented efforts to bring about a fundamental change of the underlying economic and social structure in the direction of something much better, is the Royal Project at Doi Tung.

a

The Doi Tung Development Project

Doi Tung Project Center: much to see and to learn!

Doi Tung Project Center: much to see and to learn!

Under the Patronage of the 1995 deceased Royal Mother, Princess Srinagarindra, herself an orphan from poor backgrounds, who had been admitted to the Royal Palace as a child, a Royal residence and a project center dedicated to the development of sustainable alternative livelihood options for the local population, were created on an area of altogether 150 square kilometers under a holistic and integrated approach on Doi Tung, right in the midst of the mountains of North Thailand.

The Royal Mother recognized that the prevalence of the opium cultivation and processing as well as the accompanying drug trade and consumption were primarily a symptom of the peoples’ poverty and lack of opportunities: “Development can only work, if the basic livelihood necessities are covered. Without appropriate income, the people have no other choice as to clear the forest and engage in other illegal activities such as the cultivation of opium and prostitution.”

Based on this insight, the project started with identifying income options in the areas of handicrafts and agriculture, the conveyance of relevant skills to the local population, and last, but not least, the active support of collective and individual livelihood efforts. Experts from Thailand and the entire world were consulted in order to, based on the local conditions and available skills, identify suitable handicraft products and agricultural cash crops, for whose marketing also a market would be accessible.

The Doi Tung development project maintains divisions in the fields of food, forestry, gardening and landscaping, tourism and artisan craftwork.

Introduction and spread of tea cultivation in North Thailand

Panoramic tea garden, Doi Tung, Thailand

Panoramic tea garden, Doi Tung, Thailand

ONE thing, that was brought to North Thailand by the royal development projects, which of couse is of particular interest here for us due to our theme context tea from North Thailand, is the cultivation and processing of tea plants suitable to the local geographic and geological conditions. Thailand itself and the Thais have no tradition of a tea culture. Up to the Royal Development Project’s initiative, tea was a common beverage in North Thailand only with the Shan and some of the hill tribes originating from China. They harvested tea leaves from wild growing tea trees and processed them according to their own ancient traditions to different varieties of green tea and Pu Errh style tea (for more information about wild growing tea in North Thailand see also our article “Pang Kham – Tea Village in No Man’s Land”). This situation was to fundamentally change now.

The Royal Development Projects flew experts in from Taiwan to determine, which cultivars would best the local conditions, and those experts initially recommended the Taiwanse Oolong tea cultivars Jin Xuan Nr. 12 and Ruan Zhi Nr. 17. The initiative landed on fertile ground especially with the Chinese immigrants, who had brought experience and knowledge about the cultivation and processing of tea from their home country, and for who tea was a traditional integral part of their culture. Thus, the cultivation of tea plants imported from Taiwan spread very quick in and around the above mentioned Chinese settlements, with the former opium stronghold Doi Mae Salong as the new tea capital of the north, whose sourrounding hills today appear to be mainly covered with tea gardens. (for more information about Doi Mae Salong, see also our feature articles „Doi Mae Salong – Center of Tea Cultivation in North Thailand“ and „Journey to Doi Mae Salong“. The Royal Project actively helped farmers willing to make the switch with land, training, convenient loans and tea plants managing the change-over from the opium cultivation to the cultivation of high quality teas.

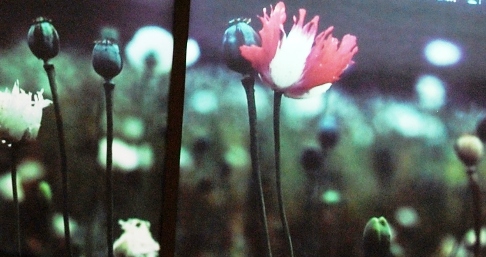

Flower of the Doi Tung Ruan Zhi Oolong No. 17

Flower of the Doi Tung Ruan Zhi Oolong No. 17

Much water has flown down the Mae Khong River since. Meanwhile, North Thailand has earned itself a name especially for its fine Oolong teas, but also green teas, and most recently, a rich and mild black tea from North Thailand have conquered many tea lovers’ hearts worldwide and established their place of origin on the world map of tea. Soon, other varieties imported from Taiwan, such 4 4 Seasons Oolong tea, Dong Ding Oolong tea and Beauty Oolong tea were to be added to the two initial cultivars. Besides these Taiwan-imported varieties, also the local representative of its species, the local tea that so far only grew wild in the mountains, was cultivated now in a more targeted manner in tea gardens now. The terms “Doi Tung Tea” and “Doi Mae Salong Tea” are about to become standards in the vocabulary tea professionals, and even tea produced by smaller producer communities such as Doi Wawee today find their way into export and thus to the world tea market. For tea connoisseurs and passionate fans of this type of teas, it has been and still is particularly interesting to witness, how the tea cultivars imported from Taiwan with time are developing their own unique character and virtually taste “like North Thailand” now.

On tea cultivation on Doi Tung, north Thailand, please also see part 2 of this article series,

The Tea Gardens of Doi Tung – On the Tracks of the Royal Development Project