Wuyi Mountains – Home of Rock Teas

River of Nine Bends, Wuyishan, Fujian, China

River of Nine Bends, Wuyishan, Fujian, China

The Wuyi Mountains are a mountain chain in the northeast of the Chinese province of Fujian. It stretches over more than 500km along Fujian’s northern border with Jianxi province. According to legend, the mountain range received its name based on the story of two brothers Wu (武 = ‘Krieg’) and Yi (夷 = ‘Barbarian’), sons of an alleged descendant of the Yellow Emperor living in the area of today’s Jiangsu at the time of the Shang dynasty (1880 – 1100 BC), who after the breakout of unrest in Central China fled to the mountains of Fujian. Today, ‘Wuyishan’ also forms the language border to the north Chinese speaking Jianxi, whereas the Min dialects spoken in Fujian are closely related to the dialects spoken in Taiwan.

In 1999, the region’s natural and cultural treasures have gained it recognition as UNESCO -World Heritage in three categories – culture, scenery and biodiversity – thus contributing to rising numbers of visitors to the region. However, the primary source of Wuyishan’s international popularity might be the famous teas coming from the area, the so-called ‘Yancha’ Oolong teas (= ‘Rock’ Oolong teas) and the Lapsang black teas. Wuyi Mountains and Anxi (in southern Fujian, home of Tie Guan Yin Oolong Tea) are alternatively cited as being ‘the cradle of Oolong teas’, whereas from a historical perspective it remains unclear, which of the two regions ultimately deserves the title, or whether the same might rightfully have to be shared instead, or be extended to the statement ‘Fujian is the cradle of Oolong teas’.

This article is dedicated to taking an in-depth plunge into Wuyi Rock Teas (chin. ‘Yancha’ 岩茶), a group of Oolong teas derived from a broad number of cultivars either native or at some point brought to Wuyi Mountains. As for detailed information about Lapsang black teas, the other famous group of Wuyi teas with famous representatives Lapsang Souchong and Jin Jun Mei, please read our article

Lapsang Souchong, Zheng Shan Xiao Zhong and Jin Jun Mei Tea – all the same?

Map of Fujian Province with focus on Wuyishan

Map of Fujian Province with focus on Wuyishan

Natural and cultural treasures of Wuyi Shan

With average altitudes between 800 and 1500 m (lowest gully 200m, highest peak ‘Huanggang Shan’ 2158 m above sea level), nutrient-rich soils and the warm and humid ‘climate oasis’ formed by the steep cliffs protecting the area against cold air from the north and east, Wuyi offers optimal conditions not only for tea cultivation. The region’s diversity of species in both flora and fauna is considered as worldwide unique. Up to 700 years old gingko trees, more than 140 bird species, as well as numerous types of reptiles and amphibians, among the more than 50, partially poisonous snakes are at home in Wuyishan’s evergreen leaf tree and conifer forests. The rugged terrain, grooved by deep pits and gullys, with 36 rock columns – the region’s major landmarks – protruding steeply into the sky, is traversed by the idyllic ‘River of Nine Bends’. The altogether 60 km long river, winding through Wuyishan at the bottom on a stretch of a deep gorge, invites for sightseeing and exploring the spectacular scenic landscape by boat on a stretch of 9 km, one of the main tourist attractions of the Wuyi core region. Other natural attractions include 72 caves, 99 steep faces and a total of 108 scenic viewpoints.

Culturally, Wuyishan looks back on a long and rich history. Archaeological finds suggest human settlement in the area reaching back up to 4000 years ago. ‘Wuyi Palace’, built in the 7th century AD as a palace for the emperor to make offerings to the deities, is well maintained and can still be visited by tourists today. For many centuries, Wuyishan served as a center of Taoist and Buddhist teachings. Findings reveal the existence of altogether 35 academies between the time of the Northern Song dynasty (960 – 1279 AD.) and that of the Qing dynasty (1644-1911), as well as of 60 Taoist temples and monasteries, of which however only rather sparse remains are left to be seen. The tea culture, in particular the cultivation and process of Wuyi Oolong teas and Lapsang black teas, has been an integral part of Wuyishan’s culture from ancient times.

Rock Tea Garden in Zhengshan area, Wuyi Mountains, Fujian, China

Rock Tea Garden in Zhengshan area, Wuyi Mountains, Fujian, China

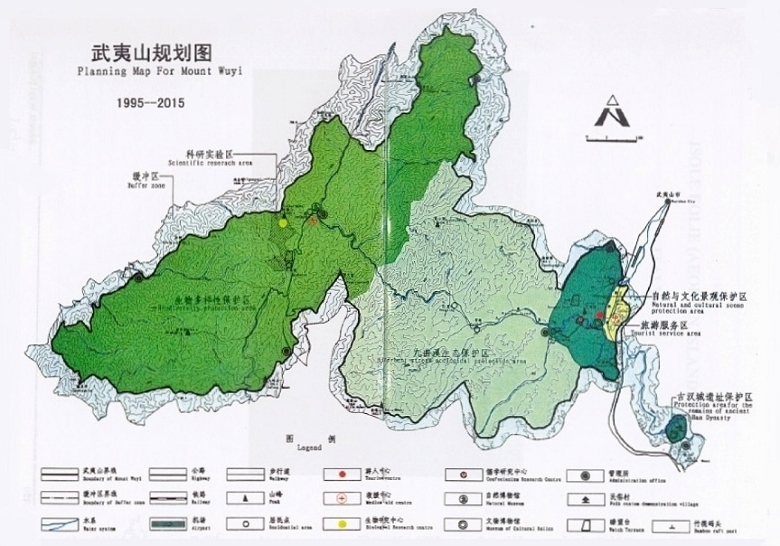

Wuyi UNESCO Nature Protection Zone and World Cultural Heritage

Since 1999, Wuyi is recognized as UNESCO World Heritage in the categories culture, landscape and biodiversity. The whole terrain covered by the program, an areal of 99,975 ha, is divided in 4 protection zones with different types and degrees of protection:

- The UNESCO Wuyishan National Nature Reserve covers an areal of 56,527 ha in the east of the Wuyi mountain range.

- The UNESCO Nine Bend Stream Ecological Protection Area with 36,400 ha covers the area around the Nine Bends River in the center of Wuyishan.

- The Wuyishan National Scenic Area covers 7,000 ha on the western end of the mountain range, including Wuyishan city and Wuyi’s most important tea cultivation territories.

- Separately, the ‘Protection Area for the Remains of Ancient Han Dynasty’ covers 48 ha of UNESCO-protected world cultural heritage a bit offside the three main parts.

The core tea cultivation territories of Wuyishan are located within the Wuyishan National Scenic Area in the western part of the mountain range. This core area is what is often also referred to as ‘Zheng Shan’ (= ‘Original Mountain’), both in the context of the delimitation of the individual protection zones and regarding the cultivation and production of Wuyi Rock Teas (Wuyi Yancha Oolong Teas) and Lapsang black teas.

Planning map of Wuyi UNESCO protection zones

Planning map of Wuyi UNESCO protection zones

Wuyi Yancha Oolong Teas (Rock Tea)

What makes a rock tea a rock tea? A frequently asked question, to which there is both a very simple and a rather complex answer. The simple answer: the rock. The specific soil properties, coined by the volcanic origins of the rock in the Zhengshan areal, are responsible for the unique mineral base note shared by all Wuyi rock teas, which outside that areal cannot eve be reproduced through cut-off proliferation of original cultivars. It is the rock and the soil of Wuyi Zhengshan that makes Wuyi Yancha Oolong teas not only unique, but also rare and expensive. However, the classification of individual tea terroirs within the Wuyishan region shows that it isn’t just that simple after all:

– ‘Zheng Shan’ (‘Original Mountain’) or ‘Zheng Yan’ (‘Original Rocks’) means the traditional core area of cultivation and processing of Wuyi Yancha Oolongs, which is identical with UNESCO’s Wuyi National Scenic Area protection zone (applies equally to Lapsang black teas). Within the ‘Zhengshan’ areal, there are several individual ‘pits’ and ‘gullys’, each of which is known for its suitability for one or more specific Wuyi Oolong tea cultivars. Originally, there were only 5 such gorges (‘3 pits and 2 gullys’) namely identified: Huiyuan Pit, Niulan Pit, Daoshui Pit, Liuxiang Gully and Wuyuan Gully. Today, however, several more specific locations within the Zhengshan area have been developed for the cultivation of Yancha teas and identified accordingly. In this context, it is interesting that the best Zhengshan tea cultivation terrains are located at relatively low altitudes of 300-700 m only. Rock, soil, and the special climate conditions within Zhengshan in general and within the gorges in particular, in combination with this level of altitude create conditions that are unique amongst notable venues of tea cultivation. It is these conditions that coin the character of Wuyi rock teas. The area adjacent to the Zhengshan zone is called

– ‘Ban Yan’ (verbally: ‘half-rock’). In parts of the Banyan areal, geological, soil and climate conditions are nearly identical with those in the Zhengshan area. These terrains are home of some traditional tea plantations, whose rock teas can be put on one level with those from Zhengshan areal – or at least close to that. Today, the best Yancha Oolongs from the Banyan area might actually even be better than Zhengshan Yanchas of lower or medium quality. Adjacent to the ‘Banyan strip’ in western direction is the

– ‘Zhou Cha’ (verbally: ‘river tea’) area, consisting of the banks of the Nine Bends River and adjacent river valley areals, blessed with fertile soils and a great wealth of water. As much as this area might be suitable for tea cultivation (and more), the Oolong teas growing here – with cultivars mostly being identical with those in Zhengshan and Banyan areas – show only little of the rock charm of Wuyi Yancha Oolongs and are not considered as rock teas in a narrower sense. Areas located beyond the ‘Zhou Cha’ zone are referred to as

– ‘Wai Shan’ (‘outside the mountain’). Also here, fine Oolong teas are cultivated, which however do not qualify as Yancha (rock tea), due to missing specific properties.

Da Hong Pao (‘Big Red Robe’) Mother Bushes

Da Hong Pao (‘Big Red Robe’) Mother Bushes

Types of Rock Teas

When learning about the numerous different tea cultivars thriving in Wuyi Mountains, yielding an equally big number of different Yancha Oolong teas, the related science easily quickly hits a degree of complexity that goes beyond the capacities of non-scientists. According to experts, there are virtually thousands of such cultivars existing only in the Zhengshan areal, some of which might be represented by no more than a few specimens. Traditionally, among the Yancha Oolongs best known in China count the ‘Si Da Ming Cong’ (‚The Four Great Wuyi Rock Teas’):

– Da Hong Pao (‘Big Red Robe’) – The ‘King of Wuyi Yancha Oolong Teas’, enjoying great worldwide popularity and demand, resulting in limited supply and prices that are unusually high even for Zhengshan rock teas. Traders often close the gaps resulting from the limited availability of original Da Hong Pao by offering more or less non-original teas labeled Da Hong Pao at lower prices. These are usually teas from the same (or a similar) cultivar grown outside the Zhengshan area. While Banyan Da Hong Pao from specific tea plantations can still rightfully be referred to as Da Hong Pao, any place of origin beyond that is a disqualifier: a tea coming from the ‘Zhou Cha’ or ‘Wai Shan’ area does not qualify to be referred to as original Da Hong Pao, whatever a trader might label it, and notwithstanding the tea’s actual quality. A typical Da Hong Pao is characterized by its particularly balanced composition of complex earthy-mineral, fruity-sweet and floral notes.

Da Hong Pao Wuyi Rock Oolong Tea

Da Hong Pao Wuyi Rock Oolong Tea

– Tie Luo Han, (chin. 铁罗汉) = ‘Iron Arhat’) is the oldest known Wuyi Yancha, whose origin reaches back to the time of the Song dynasty (960 – 1279 AD). It is a very light Wuyi Rock Oolong tea that is rather little known outside of China until today. Per standard, only the buds are picked for this tea. According to legend, it has once been created by a powerful warrior monk with golden bronze skin, which is how the name Tie Luo Han, meaning as much as ‘Iron Warrior Monk’, came about. The leaves of this tea are of particularly intensive green color, while the color of the infusion appears rather bright compared to other Wuyi Rock Oolong teas. The taste of Tie Luo Han is soft and supple, with gentle floral notes and a long lingering, sweet roast aftertaste.

– Shui Jin Gui (chin. 水金龟 = ‘Golden Water Turtle’) according to legend has received its name during the time of Qing dynasty (1644–1911), but in fact is much older than that. The importance of Shui Jin Gui rock Oolong tea for the regional culture and economy has drastically increased since the 1980s. The tea leaves are of intense dark green color, taking on a blue shimmer after the processing. The clear, deep orange infusion is characterized by a full-bodied taste with pronounced fruity (plum) note and a long lingering aftertaste.

– Bai Ji Guan (chin. 白雞冠 = ‘White Cockscomb’) – a particularly light Yancha Oolong. According to legend, this rock tea received its name at the time of the Ming dynasty (1368–1644) from a monk to commemorate a courageous cock, who had sacrificed his life when trying to safe his hatchlings from an eagle. Touched by the selfless action of the cock, the monk buried him, and that was exactly the place where little later the Bai Ji Guan tea bush grew. However, it is more probably that the cultivar has gained its name from the white appearance of its older leaves in the sun. Unlike most other Wuyi teas, the leaves of this bush are rather yellow than green or brown. Also, the taste of Bai Ji Guan has a relatively distinctive character as measured by the general likeness of Wuyi Yancha teas, and with 60-80% has a comparably low degree of oxidation.

In recent times, the two Yancha cultivars Rou Gui and Shui Xian haven risen to great popularity both in the west and in China. The two cultivars have the largest prevalence among varieties in Wuyi and today need to be mentioned in one line with the above-listed ‘Si Da Ming Cong’.

– Rou Gui (肉桂 ‘Cinnamon’) Rock Oolong Tea has started conquering the hearts of tea lovers everywhere in the world just in recent times. The intense sweetness and fruitiness of the teas produced from this cultivar might have greatly been contributing to that. My studies of Wuyi teas and Wuyi rock teas in particular didn’t clearly reveal, at what point in time and how exactly the Rou Gui cultivar has made it to the Wuyi mountains, but it seems that once there it quickly developed into a ‘Yancha’ with very strong ‘rock charm’ and that the tea’s great popularity is mostly based on that Wuyi rock tea identity. The tea leaves are of sand green to dark color and exude a lingering fragrance of Chinese cinnamon. In recent years, Rou Gui Yancha Oolong tea has been awarded a range of gold medals on national tea competitions. Rou Gui Wuyi Rock Tea

– Shui Xian (水仙 ‘Narcissus’) Yancha Oolong Tea is a traditional Wuyi Rock Oolong Tea, who has also just recently risen to greater popularity. The relatively large-leaved cultivar shows a great color variance in his leaves in a spectrum between green and black. The taste of Shui Xian Rock Oolong tea is dominated by characteristic rock tea mineral notes.

‘Lao Cong’ in the context of a Shui Xian rock Oolong tea means ‘old bush’. The Shui Xian cultivar is said to produce ever better tea with increasing age. Unfortunately, there doesn’t seem to be a common definition for how old a Shui Xian bush needs to be to be ‘Lao Cong’. On the market, the term refers to widely diverging age classes, ranging from 15 to 100 years. Therefore, without knowing the exact age of the bush, the term ‘Lao Cong’ therefor doesn’t really tell much.

For each of these Wuyi rock tea cultivars, there is exactly one place located within Wuyi’s Zhengshan area, to which its original origin is attributed. Today, individual sites are usually occupied by more than one cultivar, depending on suitability, i. e. altitude, terroir, soil and microclimate. The detailed lineages of the individual cultivars and the resulting interdependencies and kinship relations today are subject to thorough scientific study in China. Here an example quite suitable to demonstrate the topic’s level of complexity: Da Hong Pao (‘Big Red Robe’), without question the most famous of rock Oolong teas and therefor often also referred to as the ‘King of Wuyi Yanchas’, evidently originates from a set of 5 (or 6) ‘original bushes’ or ‘mother bushes’, located at an identified spot on some cliff within the Zhengshan area. However, scientific research undertaken on these bushes has suggested that in fact only 3 of these mother bushes might be genetically identical, so basically there is actually more than just one cultivar represented within this set of mother bushes. Now, while ALL tea bushes that have been propagated through cut-offs from these mother bushes (whether close to or far away from the original spot) are descendants of these mother bushes, only the specimen growing in Zhengshan area as well as some old and traditional tea plantations in the proper Banyan area might be referred to as original Da Hong Pao. Outside these territories, the cultivar will change its characteristics so significantly that the actual ‘rock tea’ properties are either diminished or even lost, so that referring to a tea coming from such cultivation as Da Hong Pao is considered as illegitimate. And similarly complex lineage situations and requirements profiles apply to all other above-mentioned Yancha Oolong tea cultivars… By the way, picking leaves from the original Da Hong Pao mother bushes is strictly prohibited and reserved for scientific purposes since 2007.

Shui Xian Wuyi Yancha Oolong Tee

Shui Xian Wuyi Yancha Oolong Tee

Handpicking and Processing vs. Machine Picking and Processing

Technological ‘progress’ in the picking and processing procedures involved in tea processing has not left Wuyishan unaffected. Also here, fully handpicked and manually processed teas, which in our opinion always have a potential to be superior to teas produced by machine processes, are becoming increasingly rare. However, they are still common in the Zhengshan areal, once due to the higher prices achieved with teas from here, making the manual work worth the effort, and second, of course, in regard to picking, because manual picking is only possible in conventional tea gardens on halfway even surfaces, and thereby not in much of the rugged terrain that is typical for the Zhengshan area.

The following explanations to the picking and processing of Wuyi rock teas are based on the assumption of fully traditional and manual processes. Where machines come into use, the statements made here must be relativated and adapted accordingly.

Picking of Wuyi Yancha Oolong Tea

The picking of tea leaves in Wuyishan is attached to a special challenge that is probably rarely known from other places in this form: identifying one’s own tea plants. Besides the modern conventional cultivation of tea bushes in orderly rows that are easily attributable to their respective owners, especially the old and particularly precious rock tea bushes in Wuyishan often grow individually or in small groups and in a widely dispersed manner and/or hard-to-access places, such as on ledges or steep cliffs (see for example the picture of Da Hong Pao mother bushes). For pickers hired on temporary basis, who are not familiar with the terrain and the details of ownership of individual bushes and areas, it can be difficult or impossible to locate individual bushes or groups of bushes belonging to their respective owner and/or employer. Therefore, it is common in Wuyishan that an owner of tea bushes will accompany his pickers, not only to monitor the appropriateness of picking standards, but also to identify the correct tea bushes in his possession towards the pickers in the first place.

Rock column ‘Yulu’ in the Wuyi UNESCO protection zone

Rock column ‘Yulu’ in the Wuyi UNESCO protection zone

In inaccessible terrain, it might in individual cases be quite tempting to pick from particularly precious bushes that are actually not in one’s possession. Generally, there seem to be quite high ethical standards be prevailing in Wuyishan in this regard. However, there is also a traditional customary law existing in Wuyishan that is applied to such cases: if somebody is caught picking from somebody else’s bushes, he will have to pay the actual owner double the value of the picked tea leaves.

Traditionally, only the top 3 tea leaves of each branch mature for picking is being picked (there are deviations from this for individual cultivars). Though this standard appears to be watered down nowadays as a result of the pressure exacted by high demand, with the tea leaves mostly being picked right down to the so-called ‘fish eye’ (i.e. ca. 5 leaves or more), the harvest brought in this way will later be sorted by hand again and the better quality leaves separated from the lower quality ones. The resulting 2 qualities will in turn be widely identical with a separation into 1st to 3rd leaf on the one side and below leaves on the other. The ‘2nd choice’ or ‘B grade’ is in this case a lower quality tea traded at a lower price accordingly. The system has the ‘advantage’ that for example there will be original Zhengshan teas available at comparably affordable price levels, while the availability of pure high qualities remains widely uncompromised.

Processing of Wuyi Rock Teas

The initial processing steps of rock teas are the same than for other Oolong teas: after the picking, the tea leaves are first spread in the open and let wither under the sun, before being brought into the half-light of the production hall, where they are typically stored in shelves on large round bamboo trays for further withering. During the withering, the tea leaves are time and again manually turned and shifted. At this, the leaf surfaces are broken up with mechanical force (traditionally by hand), in order to enable an interaction of the tea juices with air (oxidation). The visible result of this is the spotty brown coloring of the ready processed tea leaves. The reaction of the leaf juices with oxygen has effects on the tea’s taste that form an integral part of the characteristic Oolong tea taste profile. – (hereto, please also see our Video on Oolong tea processing)

All Wuyi Rock Oolong Teas are positioned in the upper quarter of the oxidation scale. Determining the exact time, when the oxidation process must be stopped is the domain of an experienced tea master. Once he considers this point to be reached, the tea leaves are heated to high temperatures (traditionally in a wok pan over wood fire) for a short period in order to ‘fixate’ them. The ensuing cycle of roasting the leaves over charcoal is a characteristic of Wuyi Yancha Oolongs. An initial roast, during which the tea leaves are also rolled into their typical long, slightly curled shape is done right away, while further roasting runs (at least one!) are scheduled depending on the availability of time and other capacities. Roast taste and aroma are tendentiously overpresent in freshly processed rock tea. High quality Wuyi Yancha Oolongs are therefore usually stored for at least 6 months before being brought on the market.

Rou Gui Wuyi Yancha Oolong Tea in our degustation

Rou Gui Wuyi Yancha Oolong Tea in our degustation

Challenges with your shopping for Wuyi Teas (Yancha Oolongs and Lapsang Black Teas)

As the above explanations show is not only the quality spectrum of Wuyi teas quite broad, as we actually know it from tea in general, but gains additional complexity through the particularly great diversity of influence factors: variety / cultivar, place of origin (Zhengshan, Banyan, etc.), age of the bush, machine vs. manual picking / processing, picking standard, processing skill and diligence, and more. Now, this wouldn’t be further tragic, if the individual properties would be consistently labeled and made available to the end customer (the tea drinker and actual concerned person) in the form of factual information. This, however, is not always the case. The described complex realities on the market are tendentiously simplified to a degree that often trespasses the thin line to false statements and labeling, in individual cases up to willfully misleading the customer. An offer on EBay, for example (there are many such offers there), where a ‘100% organic Wuyi Original Da Hong Pao’ is offered at USD 6.95 per 100g, is already per se more than suspicious, but also high prices and Zhengshan labeling are not necessarily guarantors for good quality. In the end, also here applies: you will make the best choices with the tea trader of your trust!

Our Wuyi Rock Oolong Teas at Siam Tea Shop, all original, handpicked and manually processed:

– Banyan Imperial Grade Da Hong Pao Oolong Tea

– Spring Zheng Shan Imperial Rou Gui (Cinnamon) Wuyi Rock Oolong Tea

Pingback : siamteas What Actually Is Tea, Part 2 – The 1000 Faces of Camellia Sinensis - siamteas